Fully Homomorphic Encryption Part Two: Lattice-based Crypto and the LWE Problem

22 Jun 2020Last time, we went through the overview of what FHE is, the different stages towards FHE, and the brief history of it. I think at this point, we should be pretty comfortable with understanding what FHE is and its potential applications.

We concluded the last post by alluding to this GSW FHE Scheme. It’s the 3rd Gen FHE Scheme based on the LWE Problem assumption which stems from Lattice-based Cryptography.

Although these topics might sound pretty archaic and distant, I claim that it’s actually not that hard to understand. In fact, with just simple knowledge in linear algebra, we can fully grasp the idea of the GSW FHE Scheme.

In this post, let’s together review some fundamental concept of Lattice-based Crypto and the LWE Problem so we can build up our knowledge to the actual GSW Scheme later.

A Brief Intro to Lattice-based Cryptography

So what the heck is Lattice-based Crypto? According to Wikipedia:

Lattice-based cryptography is the generic term for constructions of cryptographic primitives that involve lattices, either in the construction itself or in the security proof. Lattice-based constructions are currently important candidates for post-quantum cryptography.

Word. Lattice-based Crypto is basically the Crypto that uses lattices. Sounds like a very convenient explaination.

However, for us who don’t really understand what lattices are, this concept sounds very confusing. To be honest, I still haven’t fully grasped the definition of lattices. If we look at its definition on Wikipedia again, it involves some geometry and group theory concepts which is also hard to comprehend. I think this is probably why this topic scared away lots of pondering readers.

Therefore, I decided to take a more practical approach to introduce this concept using my own understanding of it.

Disclaimer: To more hard-core readers, my interpretation of this concept might not be entirely correct. Here I’m just trying to provide a more friendly perspective of this problem.

Integer Lattices from Basis Vectors

At this point, I would assume that we all have some linear algebra background. (If not, I highly recommend watching the YouTube series on Linear Algebra by 3Blue1Brown.)

We all know what a basis vector is - if we say a linear space has basis vectors $ b_0, b_1 $, it means that every single element in that space can be represented as a linear combination of those two vectors. On the other hand, the span of the basis vectors must also cover the entire linear space.

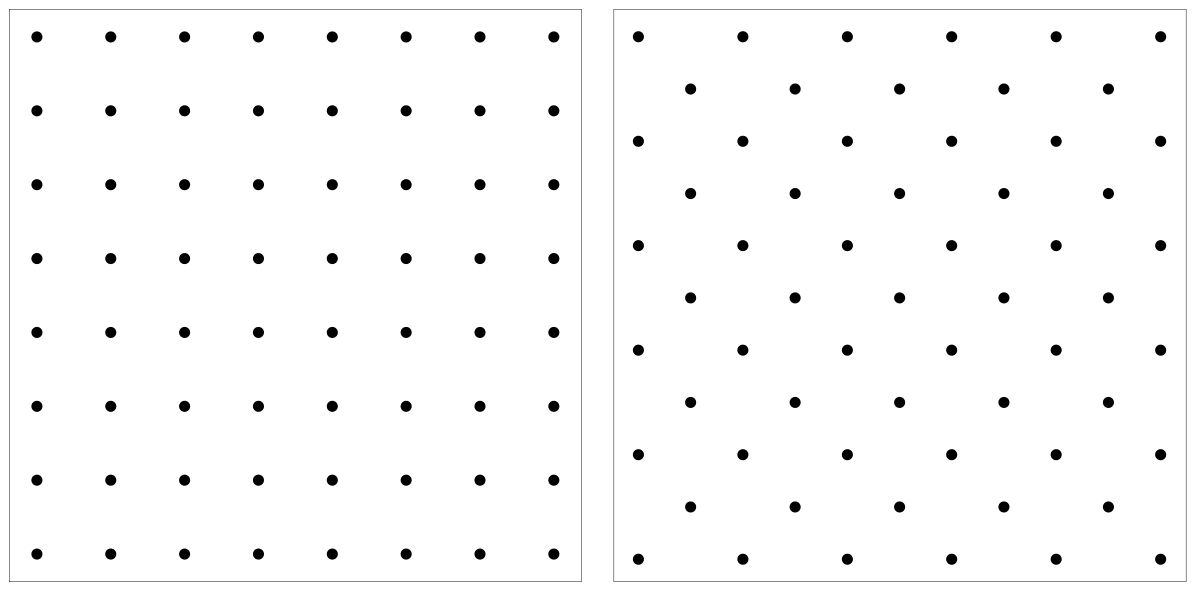

If we have some basis vectors $ b_0, b_1 $ that spans a linear space, any vector $ v $ in this space then can be expressed as: \(v = c_0 \cdot b_0 + c_1 \cdot b_1\) We know that since the coefficients $ c_0, c_1 $ can be any number, all the possible choices of these numbers will eventually create an area which represents the span of the basis vectors.

However, what if we were to add one more limitation: all the coefficients $ c_0, c_1 $ must be integers? Then, all the possible choices of these coefficients no longer create an area. Instead, they create a discrete, sparse grid of dots, where every dot represents a unique integer linear combination of the basis vectors.

To imagine this, check out the image down below:

Basically, instead of having an area of infinite vector choices, now we have a grid of finite vector choices that are linear combinations of the basis vectors of this linear space where the coefficients are all integers. We refer to this grid-like system as an Integer Lattice.

Although we are describing a two-dimensional lattice structure, it’s perfectly fine to extend it into multiple dimensions. In fact, in order to make this into a hard problem that’s suitable for cryptography, we need to have plenty of dimensions.

Interesting Problems in Integer Lattices

So what’s special about Integer Lattices? Turns out it’s the “Integer” part that makes this interesting.

Previously, when we talk about the span of the basis vectors, since the coefficients that multiplies the basis vectors can be any number, we can basically express every single vector in the linear space with a set of unique coefficients.

Now since we limit the coefficients to be integers only, we can no longer represent every single element in the original linear space using these basis vectors. Suppose we have basis vectors: \(b_0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix},b_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\) And we would like to represent the vector $ v = \begin{bmatrix} 2.6 \ 3.1 \end{bmatrix} $. There isn’t a valid pair of integer coefficients that allows us to do this.

However, here comes the interesting part: Since we cannot perfectly represent the vector with a pair of integer coefficients, what about a very close approximation? The problem becomes whether we can find a pair of integer coefficients $ c_0, c_1 $ such that the approximation of the vector in the Integer Lattice has the shortest distance to the vector itself in the lattice system. In the example above, the closest we can get is when we set $ c_0 = 3, c_1 = 3 $. The approximation vector is $ \begin{bmatrix} 3 \ 3 \end{bmatrix} $.

This problem is usually known as the Closest Vector Problem (CVP). And it’s proven to be a very hard (NP-hard!) problem to solve, once we have lots of dimensions and a handful of basis vectors. This problem serves a prelude to the Learning With Errors problem.

The Learning With Errors (LWE) Problem

Now we should have a pretty good understanding of integer lattices! Let’s switch gears for a bit and talk about the main topic of this post: Learning With Errors.

Solving Systems of Equations

Before we get into the specifics, I want to quickly do a warmup detour - a retrospection of high school algebra.

In high school algebra class, we might have encountered problems where we need to solve a system of equations. Namely, we are given a set of equations such as: \(3x_1 + 4x_2 + x_3 = 0\\ 4x_1 + 2x_2 + 6x_3 = 1\\ x_1 + x_2 + x_3 = 1\) In order to solve this kind of problems, we are taught the Row Reduction Method. Basically the idea is to use one equation to subtract another equation, so we can end up in new equations. In this example above, if we subtract the first row with the third row, we can obtain $ 2x_1 + 3x_3 = -1 $.

Eventually, after we do enough of these row reductions, if the problem is set up correctly, we can end up with some pretty nice expressions of $ x_1 = 1, x_2 = -1 $, etc. And we can plug that number back into the existing equations to solve for the other unknown variables in the system.

When we systematically learn about Linear Algebra in college, we tend to express this kind of operations in term of matrices. For example, the system of equations presented above can be converted into: \(Ax = b\\ \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 4 & 1\\ 4 & 2 & 6\\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} x_1\\ x_2\\ x_3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 1\\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\) The row reduction operation therefore, can be applied on matrices $ A $ and $ b $ to obtain the solution for vector $ x $. This method is also commonly called as Gaussian Elimination. We can formally define the Gaussian Elimination Problem to be: Given matrix $ A $, and its product $ b = Ax $, can we recover the unknown vector $ x $.

Gaussian Elimination with Noise

Since solving systems of equations is a problem taught in high school, we all know that it’s not really a hard one to solve. If the problem is well-defined, then after a few row reductions, we can easily obtain the results. Any computer can solve a well-defined Gaussian Elimination problem pretty efficiently.

However, what if the original system of equation is somehow noisy?

Namely, what if we also add an additional noise vector to the $ Ax $ product, so instead we get something like: \(Ax + e = \tilde{b}\) Where $ e $ is some noise vector that has the same dimension as the output $ \tilde{b} $. If we are given the matrix $ A $, and its product with errors $ \tilde{b} = Ax + e $, can we still efficiently recover the unknown vector $ x $?

This problem, where we are trying to “learn” the unknown vector $ x $ from its product with the matrix $ A $ with some error offset $ e $, is commonly called the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem.

If you are a careful reader, you might find very interesting similarities between the LWE problem and the CVP problem we discussed in previous sections. We are both trying to find a unique “coefficients” vector $ x $ such that it best approximates the target vector $ \tilde{b} $. The set of basis vectors in LWE is described by the matrix $ A $. Therefore, if CVP is conjectured to be NP-hard, then LWE can also be considered NP-hard under reasonable parameters, since it is a valid instance of CVP.

Now, let’s formally define LWE again.

The LWE Problem - Search Version (Formal Definition)

First, we need to introduce a set of notations for the LWE problem:

- We view $ \mathbb{Z}_q $ as integers in range $ (-q/2, q/2) $ as a finite field.

- We define $ \mid\mid e \in \mathbb{Z}^m \mid\mid_\infty $ as the infinity norm operation on vector $ e $ with $ m $ elements. The operations returns the element in vector $ e $ that has the greatest absolute value. Namely, $ \mid\mid e \mid\mid_\infty = max_i^m \mid e_i \mid $.

- Finally, we define $ x_B $ as a random variable that has its distribution bounded by a number $ B $. Namely, every sample of this random variable will definitely be smaller than $ B $. $ \forall x \leftarrow x_B^m: \mid\mid x \mid\mid_\infty \le B $.

Now, here is the formal definition of LWE: \(LWE(n, m, q, x_B): \text{ Search Version}\\ \text{Let } A \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^{m \times n}, s \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q, e \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} x_B.\\ \text{Given } (A, As + e) \text{, find } s' \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n \text{ s.t. } \mid\mid As' - (As + e) \mid\mid_\infty \le B\)

Parameters Explained

Allow me to paraphrase with my own words again.

Basically, in a LWE problem (Search Version), we need to define the dimensions of the matrix $ A $ by $ m \times n $, where $ m $ represents number of equations, and $ n $ represents the number of unknowns in the system. We also need to define the size of the finite field as $ q $, where $ q $ should be a large enough integer that is larger than any of the computations we’ll need to do. Finally, we need to define the error upper bound $ B $, so the random error we sample can be bounded in a reasonable range.

The LWE problem is basically asking us to recover the unknown vector $ s $ using the knowledge of the matrix $ A $ and the product with error $ As + e $.

Notice that we have a lot of parameters here. LWE has a lot more parameters than the other common problems we encounter in cryptography, such as the Discrete Log Problem in the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol. Here, let’s see what these parameters are really used for again:

- $ n $ is commonly referred as the security parameter ($ \lambda $). Therefore, the more unknown variables we have in the system, the harder the LWE problem becomes.

- $ m $ is usually a polynomial of $ n $. Namely $ m = poly(n) $ and $ m » n $. The larger $ m $ goes, the easier the LWE problem gets.

- $ q $ is usually $ poly(n) $. For example, we can set $ q $ to be $ O(n^2) $.

- $ B « q $, we want the error bound to be negligible to the size of $ q $, so we can properly recover the unknown vector.

Usually, when we use LWE in practice, we will predefine $ m, B, q $ as a function of $ n $, so we don’t need to manually set all these tedious parameters. Also correct initialization of these parameters can guarantee that our LWE problem has a unique solution with high probability.

From Search LWE to Decisional LWE

Notice that we keep calling the previous LWE problem construct as the Search Version. This is because in the problem we are given the matrix $ A $ and the product with error $ As + e $ and asked to recover $ s $. However, to prove security in cryptography, we usually tend to use the Decisional Version of LWE.

The Decisional LWE (DLWE) is basically the same setup as the Search Version. However, instead of trying to recover $ s $, our task becomes much simpler: to distinguish between a valid LWE problem instance versus some randomly sampled values. \(LWE(n, m, q, x_B): \text{ Decisional Version}\\ \text{Let } A \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^{m \times n}, s \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q, e \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} x_B, v \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^m.\\ \text{Distinguish } (A, As+e) \text{ from } (A, v).\) The DLWE Assumption basically states that, given an LWE problem instance $ (A, As + e) $, it is impossible to distinguish it from sampling a random vector $ (A, v \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^m) $.

The reasoning behind the assumption is fairly straightforward: Since it’s hard to recover the unknown vector $ s $ from the LWE problem instance, then this vector $ As + e $ just looks like a randomly sampled vector to us. Therefore, we can’t call the difference even if this $ As + e $ term is actually replaced by a real random vector $ v $.

The Discrete Log Problem for Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

Actually, this is not the first time we see both the search version and decisional version of a same problem in cryptography. Similar concepts were used when we evaluate the security of the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange Protocol.

Since Diffie-Hellman Protocol is based on exponentiation of group elements, the general assumption is that performing a discrete log on a group element is hard. Namely, if we are given $ (g, g^a, g^b) $, we are asked to compute $ g^{ab} $. Doing this inavoidabily involves extracting either $ a $ or $ b $ from the exponentiation, which is equivalent of doing a discrete log. We call this kind of problem the Computational Diffie-Hellman Problem (CDH).

When proving semantic security of the DH protocol, we usually prefers the decisional version - the Decisional Diffie-Hellman Problem (DDH). Namely, in this problem, we are presented either $ (g, g^a, g^b, g^{ab}) $ or $ (g, g^a, g^b) $ and another random group element $ g^r $. Our task is to distinguish whether we have $ g^{ab} $ or $ g^r $. If we cannot efficiently distinguish these two candidates if the problem is instantiated with reasonable security parameters, the DDH problem is considered hard.

However, if we want to compare the hardness of DDH and CDH, turns out solving CDH is normally harder than solving DDH. This is because of a powerful operation called the Pairing operation, which takes two group elements and maps their product of exponents into another group. (We have covered Pairings in the previous post.)

With the help of pairings, we can easily crack DDH: \(e(g^a, g^b) = e(g^{ab}, g) = g_T^{ab}\) We can simply apply the pairing operation $ e(\cdot, g) $ to the last unknown group element, and compare the result with $ e(g^a, g^b) $. If the last element is indeed $ g^{ab} $, then the equality will hold. With the help of pairings, solving DDH is trivial. Therefore, we need to make sure that the Diffie-Hellman protocol is conducted in a safe group that no Pairing operations can be done.

DLWE is better than DDH

This special property is kind of annoying, because it gives us a bad lower bound of the problem hardness. We cannot efficiently relate the hardness of CDH and DDH, and we need to be extra careful when instantiating a key exchange protocol. Therefore, we normally characterize the hardness of DDH by its average performance.

Something worth noticing here is that, the DLWE problem is equally hard as the SLWE problem. Because both problems rely on the same assumption that we cannot recover unknown vector $ s $, and there is no known attack like the Pairing operation here. This is an amazing property for cryptographic constructions. Now, we can characterize the hardness of DLWE by the worst-case performance!

Putting it all together: Regev Encryption

If you made it to this line, it means we fully understood how LWE works now. Yay!

For the next step, let’s actually put together all the knowledge we have learned so far and use lattice-based problems to actually do some cool latticed-based encryption.

One of the most prominent examples of Lattice-based Encryption Schemes is the Regev Encryption. It is invented by Regev in 2005, and it uses the standard assumptions of the DLWE problem.

Regev Encryption is an “ElGamal” style public key encryption scheme. Let’s see its formal definition.

- $ KeyGen(1^\lambda) $: The KeyGen algorithm will first create an LWE problem instance. Namely, it will sample $ A \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^{m \times n}, s \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^n, e \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} x_B^m $ and set the product with error term to be $ b = As + e $. We also need to enforce that $ q/4 > mB $ for the correctness property. Finally, it sets the private key $ sk = s $, and the public key $ pk = (A, b) $.

- $ Encrypt(pk, x \in {0, 1}) $: The encryption algorithm encrypts a single bit at a time. Just like ElGamal, it will first sample some random binary nonce vector $ r \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_2^m \in {0,1}^m $ , then it will set the first part of the ciphertext $ c_0 $ to be $ r^TA $, and the second part of the ciphertext $ c_1 $ to be $ r^Tb + \lfloor q/2 \rfloor x $. Finally, it outputs both parts $ (c_0, c_1) $ as the final ciphertext.

- $ Decrypt(sk, ct=(c_0, c_1)) $: To decrypt the ciphertext, first we compute $ \tilde{x} = c_1 - c_0 \cdot s $. Then we will check whether $ \mid \tilde{x} \mid < q/4 $. If so, we output $ x = 0 $, else we output $ x = 1 $.

Properties

The Correctness property of the encryption scheme is pretty straightforward. We can expand the computation of $ \tilde{x} $ to: \(\tilde{x} = c_1 - c_0 \cdot s\\ = r^Tb + q/2 \cdot x - r^TAs\\ = r^T(As + e) - r^TAs + q/2 \cdot x\\ = r^Te + q/2 \cdot x\) Basically, the value of $ \tilde{x} $ is the original bit $ x $ times $ q/2 $ and then overlayed with some error term $ r^Te $. Since we know that every element in the error vector is bounded by a upper bound $ B $, and $ r $ is a random binary vector, the worst case error we can get is simply $ mB $. Since we enforced that $ q/4 > mB $, we know that this error is bounded in a very small region with respect to the size of $ q $.

Therefore, we can guarantee that the decryption will always succeed. Namely, the error term is tractable and bounded by a negligible amount which won’t impact with decryption at all.

Next, we take a look at its Security property.

In order to prove that this scheme is secure, we need to use a very powerful tool in cryptographic proofs: the Hybrid Arguments.

This is really nothing fancy. Hybrid arguments allow us to achieve a certain proof via incremental steps. Let’s first construct the first hybrid, which is basically the view of an eavesdropping adversary that sees the entire encryption transcript. \(H_0 : pk = (A, b = As + e), c_0 = r^TA, c_1 = r^Tb + q/2 \cdot x\) Now, we can replace a part of the public key and arrive at the second hybrid: \(H_1 : pk = (A, v \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^m), c_0 = r^TA, c_1 = r^Tb + q/2 \cdot x\) We know that one cannot efficiently distinguish between $ H_0 $ and $ H_1 $, because of the DLWE assumption. Now, let’s further optimize $ H_1 $ and arrive at the final hybrid $ H_2 $: \(H_2 : pk = (A, v \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^m), c_0 \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q^n, c_1 \stackrel{R}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{Z}_q\) Now, we basically replaced all the ciphertext terms with random samples. Because of the Leftover Hash Lemma, we can effectively treat $ H_2 $ to be equivalent as $ H_1 $.

Finally, we combine the hybrids and arrive at the conclusion that one cannot effiently distinguish between $ H_0 $, which is the Regev Encryption transcript, and $ H_2 $, which is basically random samples that can be simulated. This proves the semantic security of this encryption scheme.

To be continued: Building Leveled FHE

To review, we first described what Integer Lattices are, and talked about the hard CVP problem. Then we switched gear to talk about solving systems of equations which can be generalized as Gaussian Elimination. After that we added noise to the problem and that gave us the Learning With Errors problem. We gave formal definition to the LWE problem along with its parameters. Next, we talk about how to transition from SLWE to DLWE, and why is it better compared to DDH/CDH. Finally, we concluded the post with an intro and proof to the Lattice-based Encryption Scheme - Regev Encryption.

And now we are here. If you made it through here, we have just gone through all the fundamental building blocks that will get us FHE!

Since this post is probably already too long, I shall conclude here. For the next post, we will take a look at how to construct a Leveled FHE scheme with noise.

Credits

Most content of this post were summarized from my notes for CS355. You can locate all the awesome lecture notes from CS355 here.

Thanks again to Dima, Florian, and Saba for teaching this amazing course!